On Saturday, December 8, 1956, 26-year-old Mary Kathryn Davies of New York City arrived in the Ashland, Pennsylvania office of abortionist Dr. Robert Douglas Spencer. Mary, a part time student at Columbia University who worked at a rheumatic fever treatment center for children, was seeking an abortion. She was a native of Minnesota.

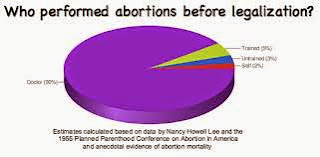

As a physician, Spencer was typical of criminal abortionists.

What was unusual about him was that rather than sneak the woman in

through the back alley, Spencer plied his abortion trade openly. Spencer was so well-known and admired in abortion-rights circles that he was dubbed "The Angel of Ashland."

As a physician, Spencer was typical of criminal abortionists.

What was unusual about him was that rather than sneak the woman in

through the back alley, Spencer plied his abortion trade openly. Spencer was so well-known and admired in abortion-rights circles that he was dubbed "The Angel of Ashland."The Fatal Abortion

According to Spencer, Mary was alone, and reported that she'd been bleeding for about two weeks. He didn't examine her, but gave her medication for pain and Ergotrate to stop the bleeding. He told her to return the following day for her abortion. Spencer didn't indicate why Mary would seek an abortion if her pregnancy seemed to be ending on its own, which bleeding certainly would indicate.Mary returned at about 10 AM on the 9th. He administered 13 ccs. of Evipal in a 10% solution to induce anesthesia. "I injected that solution into the vein of the left arm and in ten seconds she was asleep." Spencer said that the next thing he noticed was that Mary wasn't breathing. She also appeared blue. He injected five ccc. of "Metrozol"(The drug is spelled "Metrozol" in Spencer's written statement. However, my web searches for "Metrozol" turn up a veterinary medication used to treat skin diseases in fish. Spencer clearly meant Metrazol, a drug used as a respiratory and circulatory stimulant.) into her left leg. She didn't respond, so he gave her an additional five ccs. of "Metrozol", this time injecting the drug into a vein. Mary still did not respond, so Spencer attempted to resuscitate her with oxygen. He called his assistant, Mildred Zettlemoyer, into the room to assist him. With Mary in Zettlemoyer's care, Spencer went to another part of the building to retrieve adrenaline. He gave Mary three injections of adrenaline.

Mary still was not responding, so Spencer had Zettlemoyer call the laboratory assistant, Steve Sekunda, and tell him to come to the office. Spencer put a breathing tube into Mary's throat, but had to work blind because the light on his scope wasn't working. He resumed artificial respiration, "and pulled on her tongue, but got no response." By the time Sekunda arrived, at around 11:30, Spencer had concluded that Mary was dead. The puzzled man concluded "that this patient died in my office from some heart disease."

Preparing for Trial

William J. Keuch, chief detective of Schuylkill (pronounced "school kill") County detective, said that Spencer had summoned him and informed him that he and his assistant had tried to revive Mary with medications and CPR to no avail. Keuch said that when he'd asked Spencer what a young woman from New York City was doing in Spencer's office in Ashland, Spencer answered, "I'm well known in the east. I specialize in women's diseases." Women, Spencer told Keuch, came to him from all over.Spencer wasn't arrested until after 12 weeks of investigation, which included sending Mary's organs to Dr. Milton Helman, a member of the New York Medical Board, for toxicology review..

When the case was finally ready to go to court in May of 1958, the entire trial was derailed when, during jury selection, one woman asked to be excused because, she said, "I served on a jury in which Dr. Spencer was involved before." This statement was considered prejudicial to Spencer, thus tainting the other jurors.

Trial

|

| Dr. Robert Spencer |

The defense argued that the tests using the rabbit and the frog were not 100% accurate, leaving open the possibility that Mary was in the process of miscarrying. The argument evidently worked; Spencer was acquitted.

Speculations

Patricia G. Miller, author of The Worst Of Times, asked another doctor, "Dr. Bert," who had practiced before legalization, to review news reports of Mary's death and speculate as to whether Mary would have died had abortion been legal."Dr. Bert" faulted Spencer for not having an assistant while he was administering general anesthesia. "In my view, to give a general anesthetic alone is below good medical care, even in those days." He speculated that Spencer had not had an assistant working with him due to the law against abortion -- an odd speculation, since Spencer was doing abortions quite openly, with at least one member of his staff present in the building. It's also an odd speculation considering how many legal abortionists have had patients die from anesthesia complications, either due to inadequate supervision of the anesthesia process or inadequate resuscitation efforts.

Spencer's Response

Spencer's widow, Eleanor, told Patricia Miller that her husband had been quite stricken by Mary Davies' death. He continued to perform abortions, however, along with his regular medical practice, up until the trial. He was acquitted on all counts, likely because it was impossible to prove that Mary hadn't either miscarried during those two weeks of bleeding prior to her appointment with Spencer, or been aborted by somebody else. No mention is made of any fetal remains being found in Mary's body or in Spencer's office.Spencer briefly stopped doing abortions after the trial, "for a month or so," his widow said. But he resumed his business and eventually got entangled with a fellow named Harry Mace who set up a business for himself rounding up abortion patients and bringing them to Spencer. Spencer's widow lamented that Mace flooded Spencer with patients, pressuring him to rush through abortions. Spencer's health began to fail. He was arrested again, due to the attention from Mace's activities, but died before the case went to trial.

Mary Davies is the only woman known to have died from abortion related complications under Spencer's care. Spencer is estimated to have performed between 40,000 and 100,000 abortions.

Spencer in Context

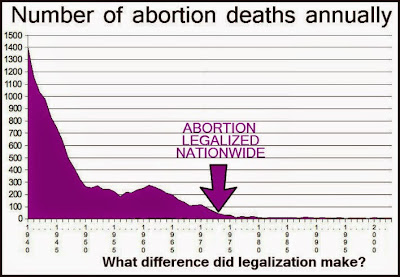

During the 1950s, we see an anomaly: Though maternal mortality had been falling during the first half of the 20th Century, and abortion mortality in particular had been plummeting, the downward trend slowed, then reversed itself briefly. I have yet to figure out why. For more, see Abortion Deaths in the 1950's.For more on pre-legalization abortion, see The Bad Old Days of Abortion.

No comments:

Post a Comment